Sara Cwynar

Writing,I conducted this interview with Sara Cwynar in the magazine issue that served as the catalogue for the 2017–18 exhibition Subjektiv. It was published as “Making Mechanisms Clear.”

You have spoken in the past about trying to build a sense of “the outmoded” into your work—to appreciate that fashions and tastes change and that the reception of your work will change over time. Have you thought about this differently in recent years as opportunities have arisen to present your work in new contexts?

I sometimes think about when many people will see the work versus very few. More often, though, geographic and social contexts seem important. It’s more than art school versus commercial gallery versus art fair; it’s also Canada versus America versus Europe. For Americans, the objects I collect and then photograph are personal, they carry nostalgic resonances. In the European context, these same objects are only vaguely recognizable, somewhat familiar.

For example, I have been collecting objects that are slightly phallic in their appearance: vacuum parts, weird pantyhose liners, old hot-water bottles. They’re abstract enough that you cannot pinpoint their original use, and therefore they take on symbolic meanings. And I think this happens more often when my work is exhibited in Europe, where the distance from the American-made objects I use is a little greater.

There is a separate narrative that attaches itself to the photographs when they are presented in America: the depicted objects speak to the history of American manufacturing, a mid-century idealism about progress and consumer society that turns into a story about what we no longer make in this country. That happens all over the world in a global economy, but these changes are a prominent part of American social and political discourse. And, too, there is an identifiably American way of buying and discarding objects. Canada, where I’m from, seems like a middle ground for my work—the response to it contains elements of both the American and European reactions to it. I’m fascinated by the slight shifts in resonance objects have between Canada and the United States.

As a Canadian artist who moved to New York then attended graduate school in Connecticut, can you elaborate on that last point, or about the “Americanness” versus “Canadianness” of your work?

Well, I’m obsessed with the American context. A lot of stuff I’ve been finding lately comes from eBay vendors in the Midwest. The region seems to have troves of commercial objects—and a greater range of them seem accessible than in places like New York or California, where cycles of fashion revolve more quickly and consistently.

I also think the objects I reference are usually American, too, and transmit an American view of the world—one filtered through pop culture and popular photography. Looking critically at not only mass-produced objects but also mass-produced modes of depiction is a kind of political project. And one that I think speaks to where American society is now, in terms of a more general awareness of how images are constructed. Canada just doesn’t feel as mixed up, for lack of a better way of putting it, and it doesn’t feel as loaded to investigate these kinds of objects there.

Much of your source material was originally made or printed during the late 1960s and early 1970s, a period you describe as bringing a certain mid-century idealism to its conclusion. Does the present moment also seem like a point of transition or inflection?

I think it does. For example, the reason I wanted to make a project about the rose-gold iPhone is that I believe it exemplifies so many of the qualities that objects from that earlier period represent. For one thing, selling something purely around a color—a color “invented” for an object—feels very much of the 1960s-’70s moment. Corporations and designers re- appropriated colors for commercial uses all the time. There’s also something resonant about how the rose-gold iPhone is the same as another, more commonly available iPhone; it simply has a new veneer. That feels like a “modern” way of selling something—a very idealistic way of pitching a product.

I wanted to point to the way you can look back at that time and see its crass commercialism so clearly. The distance permits a certain cynicism about the mechanisms for selling products. You can even acknowledge how those practices led us to where we are today. But despite our sophistication, the same forces are in play today—even if we believe we can see through them. I wanted to talk about the iPhone party because it totally got me; I was seduced by it. I wanted to think through my personal relationship to these broader forces. Even though you see things clearly, even if you’re inherently skeptical, you sometimes can’t help but participate in them.

You’ve begun making videos. How does their durational nature, the possibility of their narratives changing or even corroding over time, correspond to your thinking about these decades-long changes in society?

I want to revisit some of the advertising strategies I critique in my photographs, but only reveal that critical stance slowly. Perhaps viewers won’t realize, at first, that what they’re seeing is not exactly what it looks like.

Speaking procedurally, I wanted to make videos because I wanted to present projects featuring rapid editing. I was imagining hypothetical viewers who can only pay attention for one second before needing something else to look at. Those people exist now; rapid cuts fulfill the expectations of a certain kind of present-day viewer. Attention spans are so short; I can feel how short mine is. I thought that a rapid-fire structure made sense for showing all these objects that have themselves faded away from popular consciousness. I give each of them only a moment in the spotlight before moving on to something else. That frantic progression feels to something like today’s advertising feels, or how being in the world feels.

We likewise live in an era of seemingly sped-up news cycles and political developments …

The cycles are so fast. I think about the rose-gold iPhone in the context of the soft jewelry boxes that are featured in Soft Film. Those boxes likely had a decade or two of use and relevance. The rose-gold iPhone already feels like it’s falling out of favor, or as if it’s out of date. It’s much more accessible today, and therefore less desirable, than when it was first introduced and cost something like $800.

I give each object only a moment in the spotlight before moving on to something else. That frantic progression feels to something like today’s advertising feels, or how being in the world feels.

Perhaps this is why your video never shows the rose-gold iPhone, except in an image you recorded off of a screen …

I purposely never put it in the film. I actually have a rose-gold iPhone now because I was entitled to an upgrade through my phone plan. I was using a mangy, cracked iPhone 5 for at least a year, so that’s what’s lovingly held and touched in the film. I could barely see its screen.

Your hands hold the phone in the film, and elsewhere a narrator describes you as owning a “collection of pictures of women demonstrating technology.” Is that one way you conceive of your work, as demonstrating or revealing technologies?

That’s definitely part of my work. I want to make mechanisms clear, which is perhaps even more important given how technically sophisticated art photography often is. The barrier to entry for art photography, in terms of access to technology, can be high. I have always been interested in making things that don’t require such technologies. Or perhaps deliberately misuses them, creates something filled with more mistakes than what I initially thought was “real” art photography, like Jeff Wall or Andreas Gursky.

Do you think that’s partly a generational divide?

The way I work seems more prevalent in the last five or ten years, when photographers were making more low-key work, making art within their economy of means, making photographs as photographs, not as monuments. I don’t know whether that’s a response to the moment, or to the art market, or whatever, but it feels like the most vital aspects of art photography have moved away from epic projects. What can Gursky do today to surprise us?

He could incorporate bodies! In the past two to three years you’ve begun making portraits. Can you discuss the relationship between the people depicted and yourself, or between the people depicted and the objects that surround them?

I photograph people like I photograph objects. I’ll take a portrait and then, at least when it’s printed and placed into an arrangement with other objects in the studio, it becomes part of a still life.

Everyone I photograph though is someone I am close to and know well. I photographed my ex-boyfriend a lot, and he appears in both of my recent films. Having someone in the film with whom I have a close relationship helps to temper some of the dry theory that makes up part of the narration. Just when you can’t listen to any more of this academic language, the film shifts into a more personal register.

Tracy, who appears in several recent photographs, has been my friend for about ten years. She is an art director who currently works at Google. She poses with a deep knowledge of how women have been represented in pictures down the ages; she poses almost ironically. Everything she does is familiar but a little off. She’s a great collaborator with whom to think about a critique of the traditional representations of women. The photographs of her look to me like mid-century studio portraits. It was nearly always white women who featured in such commercial portraits during that time. It still feels notable to see that kind of picture featuring someone who is not white. Conversely, using people close to me also helps me to find my way into archives that I don’t know much about. I connect images I find seductive to aspects of my own life. We can work together to find new meanings for historical precedents.

Many photographers who work this way, who make advertising-style images, such as Roe Ethridge, Torbjørn Rødland and Christopher Williams… their work is always perfect. I know that’s what advertising imagery is supposed to look like, but I think it’s more exciting when pictures are not perfect. I don’t know how to make a perfect picture. I bought a digital Hasseblad, which makes everything look so seductive, and I can’t find a way to use it for my own purposes.

In Soft Film, your body is presented alongside objects, it contorts to accommodate objects like plants. Yet your voice is one of authority. It’s a question literally raised in Rose Gold, whose overlapping male and female narrators. Can you speak about authorship and your visual and aural presences in the videos?

For Soft Film I cast an amazing actor, one who is way too talented to be recording voiceovers. But he wasn’t allowed to do other work while studying at Yale. I wanted a voice of authority. I was thinking of National Film Board films that lecture audiences about things in the world. I watched one last night about the Toronto police force. The level of surety in those narrators’ voices is redolent of another era. So I hired someone with a smooth voice, someone who could project that authority, but then gave him a script about which he was unsure and left in some of his hesitations and my interruptions. Some viewers may recognize the name lines drawn from feminist texts, or connect the more personal observations to other aspects of my work. But I wanted it to be quite clear, at certain points, that I am in charge.

I also think using a male voice when you’re a woman lets you get away with saying more without it feeling diaristic. Well, maybe it still does a little bit. But I believe there is still a way in which viewers will simply accept a male voice reciting “facts” in a way they won’t accept from a female voice. It’s an interesting tension in a feminist film.

Funny, I thought you were going to say … lets you get away with saying more without it feeling strident or bitchy.

I hadn’t thought about it that way, but that feels true, too.

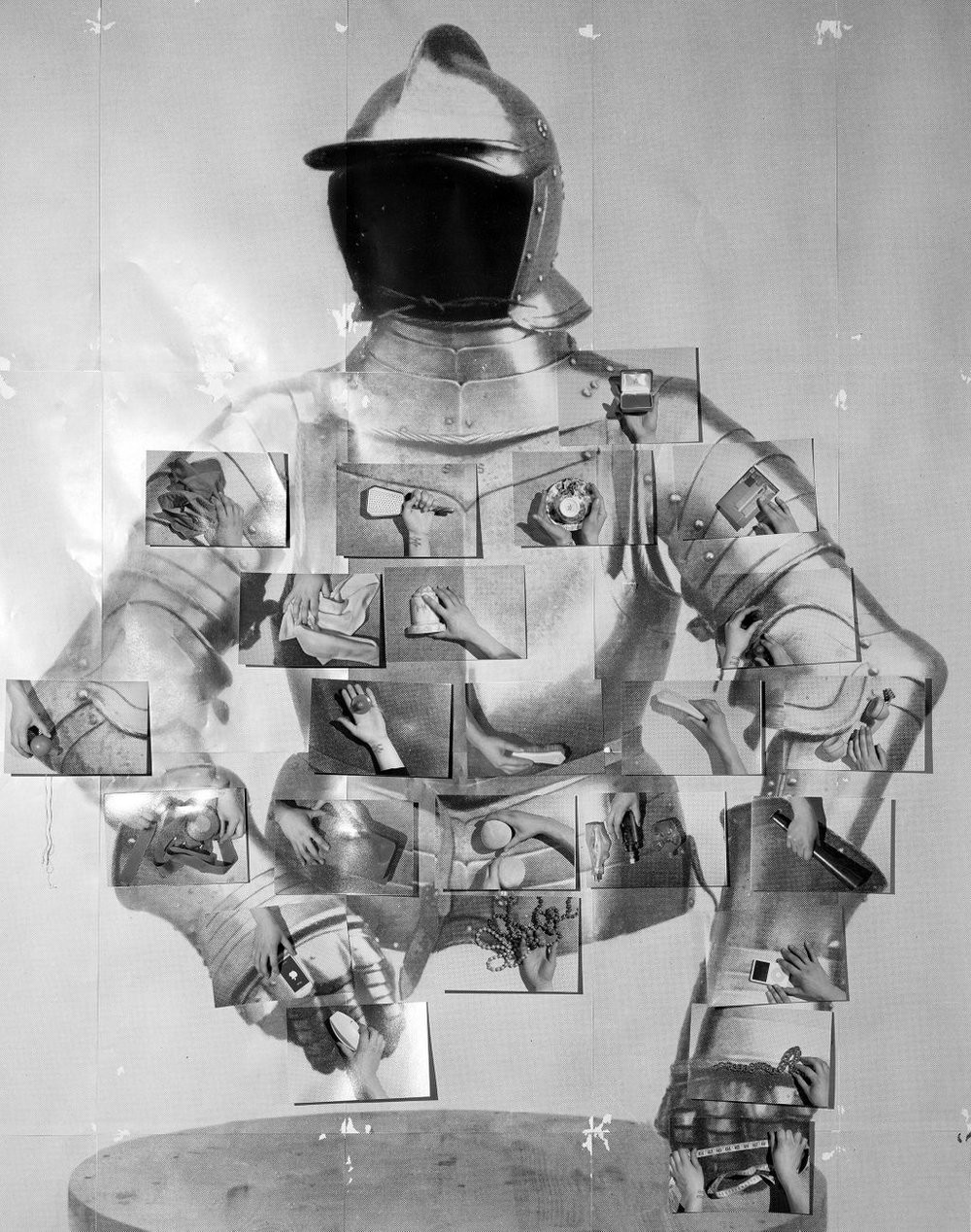

We’ve been speaking about bodies and voices. Can you tell me a bit about your recent pictures of armor, which are about a kind of bodily absence?

I found those pictures at the York University Library in Toronto. I wanted something to reiterate the New York exhibition’s themes of technology and the masculine-feminine dialectic—you know, Tracy versus the presidential busts and the armor.

I think they’re creepy pictures. They come from an out-of-print book on armor that I’ve never seen anywhere else. It hadn’t been checked out of the library since the 1970s. And the pictures themselves are from the 1950s. They were made with an eight-by-ten-inch camera, and the staginess of the lighting somehow makes them look futuristic, almost as if they were 3D modelled. They represent a mashup of time periods and technologies even before my own interventions. I inserted more objects, ones that are often coded “domestic” or “female” to offset the seemingly stoic male figure we imagine inhabits the suit of armor.

Can you elaborate a little more about the female/male dialectic in your recent exhibition? It seems like the live presences in your work are female and the more absent, colder presences are male.

Except for Bernado, my ex-boyfriend, who appears briefly in the film. But I guess I was thinking about women—about many different groups, in fact—being affected by abstract male forces. I had already begun the work when the image was published of dozens of white men sitting around a table at the White House discussing women’s reproductive rights. Power can be so abstracted, so removed from the places and the people who feel its effects.