Kentucky Renaissance

Book,This book is the catalogue that accompanied my 2016–17 exhibition of the same name at the Cincinnati Art Museum. It grew out of an idea I first had in 2011 to understand the links between remarkable artists in Kentucky’s capital city. I was pleased when John Jeremiah Sullivan, who has written eloquently about other Kentucky subjects, agreed to contribute. The book was co-published by the Cincinnati Art Museum and Yale University Press. It can be found on Yale’s site, on IndieBound, on Amazon, or via WorldCat.

The text here is excerpted from “Assembly Required,” my essay in the book.

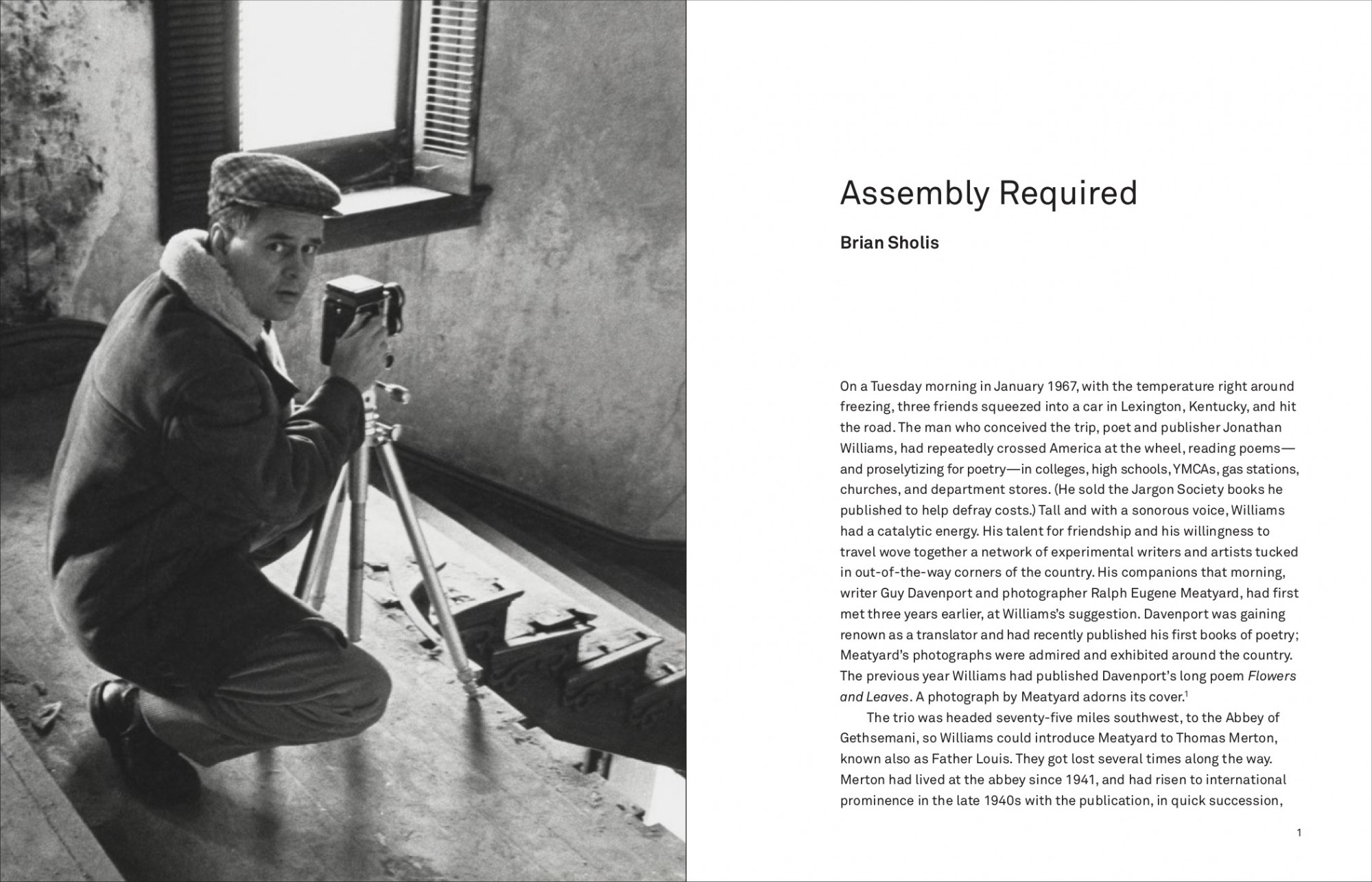

On a Tuesday morning in January 1967, with the temperature right around freezing, three friends squeezed into a car in Lexington, Kentucky, and hit the road. The man who conceived the trip, poet and publisher Jonathan Williams, had repeatedly crossed America at the wheel, reading poems—and proselytizing for poetry—in colleges, high schools, YMCAs, gas stations, churches, and department stores. (He sold the Jargon Society books he published to help defray costs.) Tall and with a sonorous voice, Williams had a catalytic energy. His talent for friendship and his willingness to travel wove together a network of experimental writers and artists tucked in out-of-the-way corners of the country. His companions that morning, writer Guy Davenport and photographer Ralph Eugene Meatyard, had first met three years earlier, at Williams’s suggestion. Davenport was gaining renown as a translator and had recently published his first books of poetry; Meatyard’s photographs were admired and exhibited around the country. The previous year Williams had published Davenport’s long poem Flowers and Leaves. Photographs by Meatyard adorn its front and back covers.

The trio was headed seventy-five miles southwest, to the Abbey of Gethsemani, so Williams could introduce Meatyard to Thomas Merton, known also as Father Louis. They got lost several times along the way. Merton had lived at the abbey since 1941, and had risen to international prominence in the late 1940s with the publication, in quick succession, of the autobiographical The Seven Storey Mountain and the penetrating Seeds of Contemplation. Merton’s plainspoken accounts of his life and spiritual journeys endeared him to millions of Catholics at a time of great change in the church, and his literary style prompted admiration from secular readers as well. Though he had been cloistered in a hermitage since 1965, Merton’s fame brought many visitors to his door.

The car deposited its passengers at Gethsemani in late morning. Merton’s quarters were “a nice comfortable little cabin out in the woods, out from the monastery,” as Davenport later recalled. “It was heated by an oil stove, I think. Bathroom was still an outhouse.” The men sat down to “a four-hour winter conversation over Trappist cheese and bread with bourbon from one of the distilleries nearby.” Here, at a Cistercian monastery nestled into the stony hills of central Kentucky, was an unlikely confluence of figures: four men of disparate backgrounds, each a confident artist, each attuned to new developments in poetry, philosophy, and art. They had come to Kentucky for different reasons: Davenport to teach English at the university; Meatyard to work for an optician; Merton to retreat from the world and pursue his spiritual calling. Williams recognized remarkable figures and wanted to forge relationships among them, so he visited from North Carolina frequently. As Davenport later said, “Jonathan knows at least five people in every town in the United States. There is no such thing as being too small for Jonathan.”

Their conversation that day must have ranged widely; certainly poetry, a shared passion, was one subject, and another was Meatyard’s photographs, which Merton immediately admired. (Merton had pursued photography with increasing avidity since the early 1960s.) Perhaps Meatyard and Merton also discussed Zen Buddhism, a subject they had arrived at from different places. Merton came to Buddhism in his attempt to better understand Christian mysticism; photographer Minor White had introduced Meatyard to the philosophy in 1956, recommending books on Zen.

Whatever the subjects of their conversation, the introduction was a success. Writing in his journal the following day, Merton confided, “The one who made the greatest impression on me as artist was Gene Meatyard, the photographer.” Meatyard felt similarly: “We hit it off famously from the first. Our interests were all the same, some more avidly in one area, some another.” The two men began a correspondence and paid visits to each other. Writing to Merton in August, Meatyard suggested a novel endeavor: “Would you be willing to try something in an experimental vein? … What I propose is to see how closely I, or any artists [sic] can connect with the utterances of another. If you were to send me words, prose or poetry and number of words doesn’t matter and I don’t necessarily understand the personal or private meaning of them—then try to make a photograph … of them? We might also if that works try my abstracted photo first and then your words.” Three days later Merton responded: “I like very much your suggestion of trying something experimental; poems and pictures. Let’s think about that.”

Meatyard’s openness to experimentation of this sort was due in no small part to another encounter more than a decade earlier, one that would place him on the creative path he followed until his death in 1972. It likewise reshaped the artistic community in Lexington, helping to forge a group of photographers whose talents have been vastly underappreciated during the past forty years. Meatyard has been the subject of several museum retrospectives and numerous critical assessments, securing his place in the pantheon of leading American photographers. His soaring reputation, rightly deserved, has largely separated him from the immediate context in which his work developed. This has created at least two side effects that should be addressed. The peculiar, uncanny characteristics of his best-known photographs, combined with our unquenchable thirst for narratives of solitary artistic genius, have remade a cosmopolitan artist and dedicated mentor into a backwoods folk hero. And the varied and powerful work made by his peers and friends, which Meatyard himself acknowledged repeatedly as important to the story of photography, has gone largely uncelebrated beyond the region. Placing Meatyard’s achievements back in their proper context redresses both unfortunate circumstances, and helps recover a truer understanding of the internal dynamics of this remarkable artistic community. These were not just friends; they had a club. It met monthly, and when Meatyard joined, the story took a fascinating turn.