Edward Steichen

Writing,Edward Steichen’s photographs for the Stehli Silks Corporation surprised and delighted me when I first discovered them. Several years later I had the chance to write about them. Published in OSMOS 5, Fall 2014.

As it steamed across the Atlantic one day in 1926, the Isle de France was the site of a chance encounter. Ruzzie Green, at the time an illustrator and designer, was on his way to Europe, perhaps to the Swiss headquarters of the Stehli Silks Corporation, where he served as art director. On deck he chanced upon Edward Steichen, the artist whose pictures were revolutionizing fashion photography. The two struck up a conversation, and, in short order, a deal: Steichen would contribute designs to Stehli’s popular “Americana” line of fabrics. The fruits of their collaboration, when released to the public the following spring, would prove to be not only a commercial success, they would also draw together a remarkable number of aesthetic, social, and economic trends: celebrity, artistic abstraction, mass production and consumption, the creative appropriation of everyday consumer objects—in short, much of what we identify with modern American society and culture.

Green and Steichen’s meeting came at an auspicious moment. Historians of American culture, including Lizabeth Cohen and William Leach, have described the mid-1920s as an era of standardized production, mass consumption, corporate expansion, and increasingly influential advertising. America had emerged from the wreckage of World War I relatively unscathed and the stock market crash was still a few years away. Five-cent theaters featuring ethnic films were losing ground to the Hollywood system; mom-and-pop shops were being displaced by department stores and national chains. Recognizable brands were being promoted by familiar names and faces.

Stehli’s “Americana” line capitalized on these transformations, deploying celebrity name recognition to sell its mass-produced textiles. Green hired nearly one hundred prominent figures to create—or at least lend their names to—these patterns, which were sold by the yard for dressmaking and other domestic applications. Participants included Helen Wills, an eight-time Wimbledon champion, the cartoonist John Held, Jr., and the fashion designer Pierre Mourgue.

The fruits of Steichen and Stehli’s collaboration would prove to be not only a commercial success, but also draw together a remarkable number of aesthetic, social, and economic trends

Green commissioned dozens of artists to create modernist patterns for Stehli, but Steichen was the only photographer who contributed to the “Americana” line. His popularity among fashion cognoscenti and his willingness to collaborate with others made him a natural fit for the endeavor. Already recognized for his talents, he had returned to New York in 1922 and was soon hired as the chief photographer at Condé Nast. Working in collaboration with Nast and Edna Woolman Chase, Condé Nast’s top editor, Steichen had introduced the clarity and clean lines of photographic modernism to a field still in thrall to the soft-edged Pictorialism of his predecessor, Baron Adolphe de Meyer. Steichen was committed to joining the visual language of modern art to commerce, and would, in addition to his work for Stehli, design glass for Steuben and pianos for Hardman, Peck, and Company.

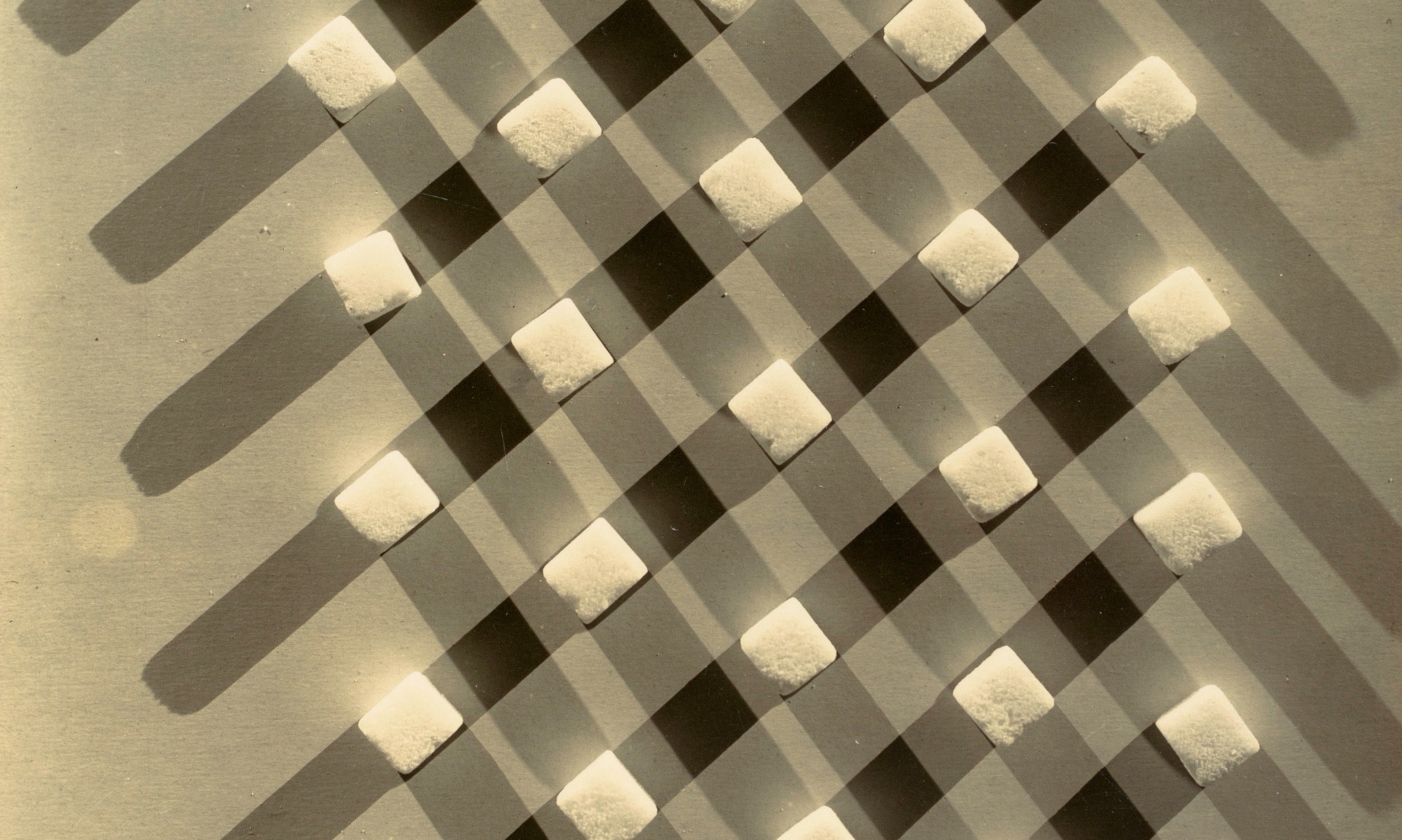

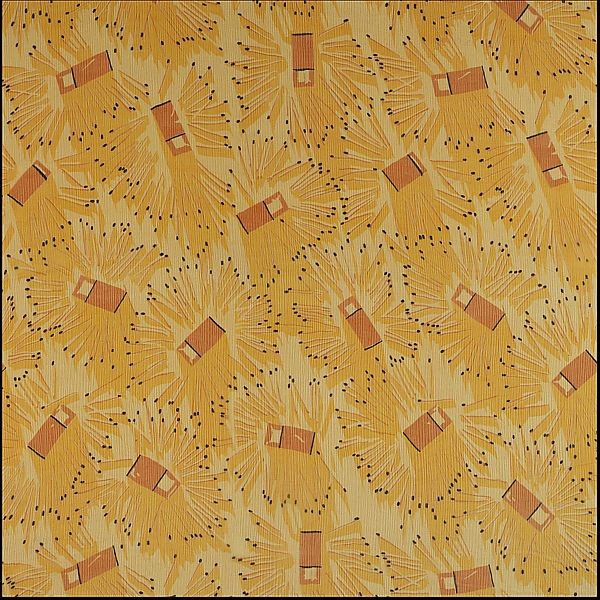

As with the creative collaborations that characterized his magazine work, in making his textile patterns Steichen built upon experiments Stehli’s art director Ruzzie Green had attempted himself. Gathering together small-scale common objects—sugar cubes, mothballs, carpet tacks, beans and rice, and the like—Steichen arranged them into grid-like patterns on a seamless backdrop. It was through his artistry, in particular his ability to control dramatic lighting, that Steichen turned these objects into semi-abstract patterns that, he felt, were “justifications of the Machine Age.” They were successful as commercial products, yes, but he also believed they were successful as art—that the force of his attention elevated these pedestrian goods and encouraged others to see in them similar aesthetic qualities. Steichen would thank Green for enabling a new way of working, writing on the back of a photographic print: “To Ruzzie … for opening up this beautiful opportunity into a new field of photography. This sounds pompous, but ‘taint meant that way.”

Indeed, Green, or someone else at the Stehli Silks Corporation, understood Steichen’s achievement and donated samples of his textiles to the Metropolitan Museum of Art the year they were produced. Looking at the fabrics now, it’s easy to see why. These angular compositions of small, geometrically shaped objects have an Art Deco flair, and Steichen wasn’t afraid to break the rhythm of the grid if it added dynamism to the overall composition. He lowered his spotlights to table level, causing nearly flat objects to cast shadows, thereby broadening the tonal range of the photographs and adding further variety to the compositions. Stehli then printed these patterns in a number of color combinations. A grid of sugar cubes appears first in navy, tan, and sea-foam green, then in brown, olive, and lavender; an arrangement of coffee beans and rice appears in bright red, pink, and black, or in turquoise, deep blue, pink, and green; a swirling pattern of buttons and thread was printed in at least six different color combinations.

“My motivating impulse as a photographer is purely objective,” Steichen asserted in July 1927. “Unless this effort, when achieved, can reach people, it will be dead. It must gain its vitality by being projected into the lives of man, and this is being brought about through the use of modern mechanics, in short, through industrialism.” Steichen, in collaboration with Green, was using technology to distribute photography through new avenues. Today, new, inexpensive printing technologies like Print All Over Me and Zazzle are allowing a new generation of artists to mass-produce and distribute their images on clothing. And an altogether different cohort of photographers is returning to the craft of studio experimentation to make abstract compositions and other formal experiments that Steichen himself would celebrate.

It’s easy to comprehend the artfulness of Steichen’s pictures, and the textiles created from them. What’s harder to appreciate now, and what remains radical about the collaboration, is just how popular Steichen’s creations were and how unusual they were for their time. Thousands of women across the country bought fabrics featuring semi-abstract arrangements of rice and beans or carpet tacks, then turned them into dresses. Such engagement by the public was enabled by Green’s twin observations: that women’s taste was increasingly sophisticated, meaning that “conventional florals and polka-dots” could be left behind; and that artists were increasingly aware that there was “drama in the American scene which could be given a wider expression.” No artist working for Stehli would give better expression to this drama than Steichen.