Moyra Davey

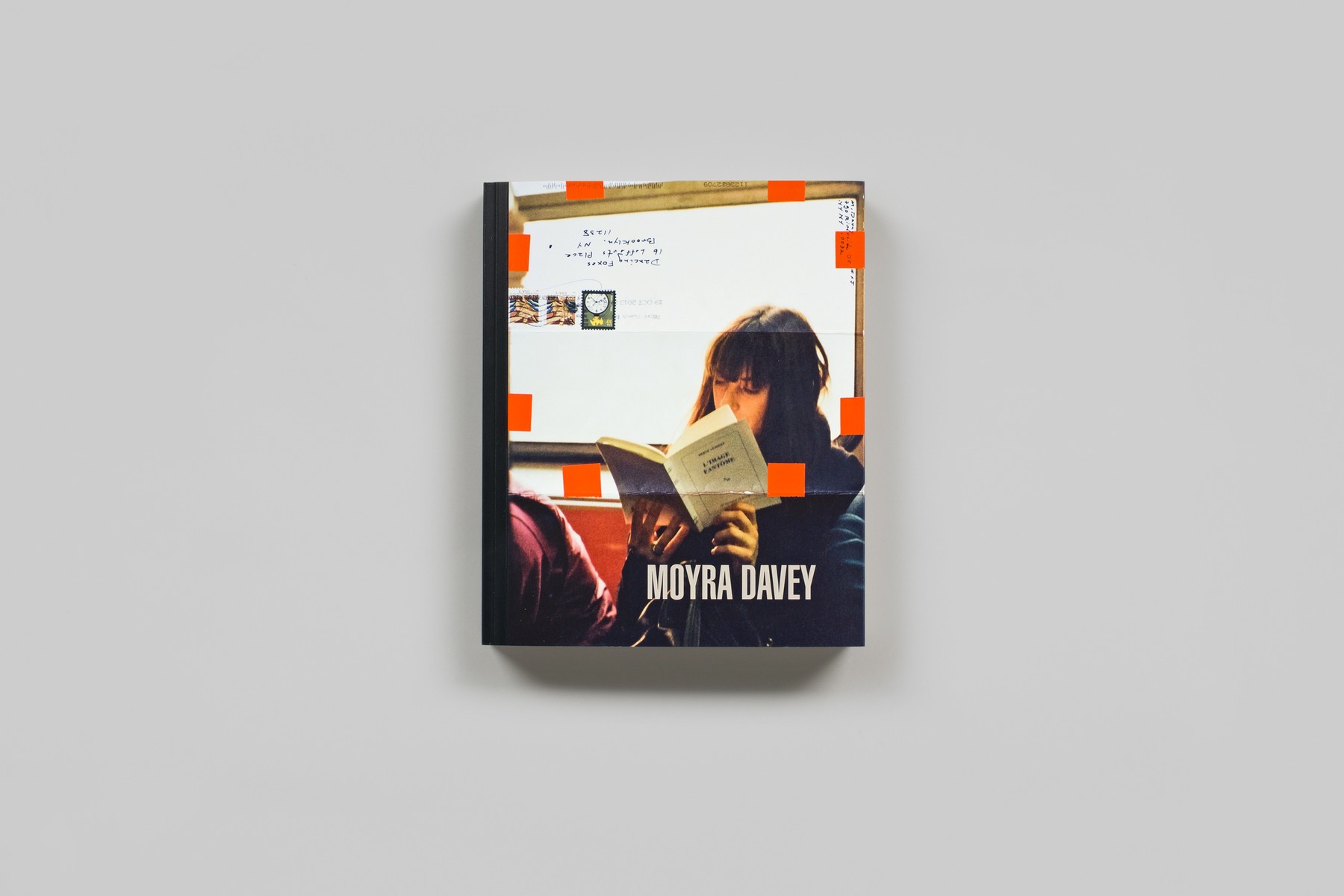

Writing,After nominating artist Moyra Davey for the 2018 Scotiabank Photography Award, which she subsequently won, I was invited to write the introduction to the book that comes as part of the prize. The book is the first to include numerous examples of both her artworks and her writings, and features multiple interviews with the artist.

Published as “Lifetimes” in Moyra Davey (Scotiabank/Steidl, 2019).

In an essay about the Reverend Francis Kilvert’s nineteenth-century journals, the writer William Maxwell conveys the texture of Kilvert’s life through a deft literary ploy. “Kilvert boarded comfortably with a Mrs. Chaloner,” Maxwell writes, “and his life in Clyro went by in, roughly speaking, this fashion: On Sunday, he preached, when and where he was needed.” Maxwell then shares brief stories from the many Sundays recorded in the diary before proceeding to Monday, to Tuesday, and on through the week.

On Thursday he “woke at 3 A.M. and looked out Eastwards. The sky clear as crystal and cloudless.” […] Or it is a week later, and the falling white blossoms of the clematis drift at the open window. […] Or it is still Thursday, and not June but October. All the glass is smashed out of the window of the low loft. […] Or it is July, and instead of dire poverty we get a dinner party at Clifford Priory.

Maxwell concludes this recounting, in which nearly a decade fills no more than four pages: “So, for seven years, his days proceeded.”

The book you are now holding, which gathers many of Moyra Davey’s photographs and writings of the past forty years, brings a similar sense of compression and the texture of lived days. What it lays bare, for me, is the manner in which Davey’s creative work represents intimacy and interiority. This is not the same thing as a diary and should not be confused for one. Instead, her photographs and videos meditate upon how we value—and work through assigning value to—what makes up our lives: family, friends, what we read, the objects that sustain us and nourish our sense of ourselves. In her 2006 video Fifty Minutes, Davey suggests that we might “infer the complexity of a life from a handful of very selective and superficial details.”

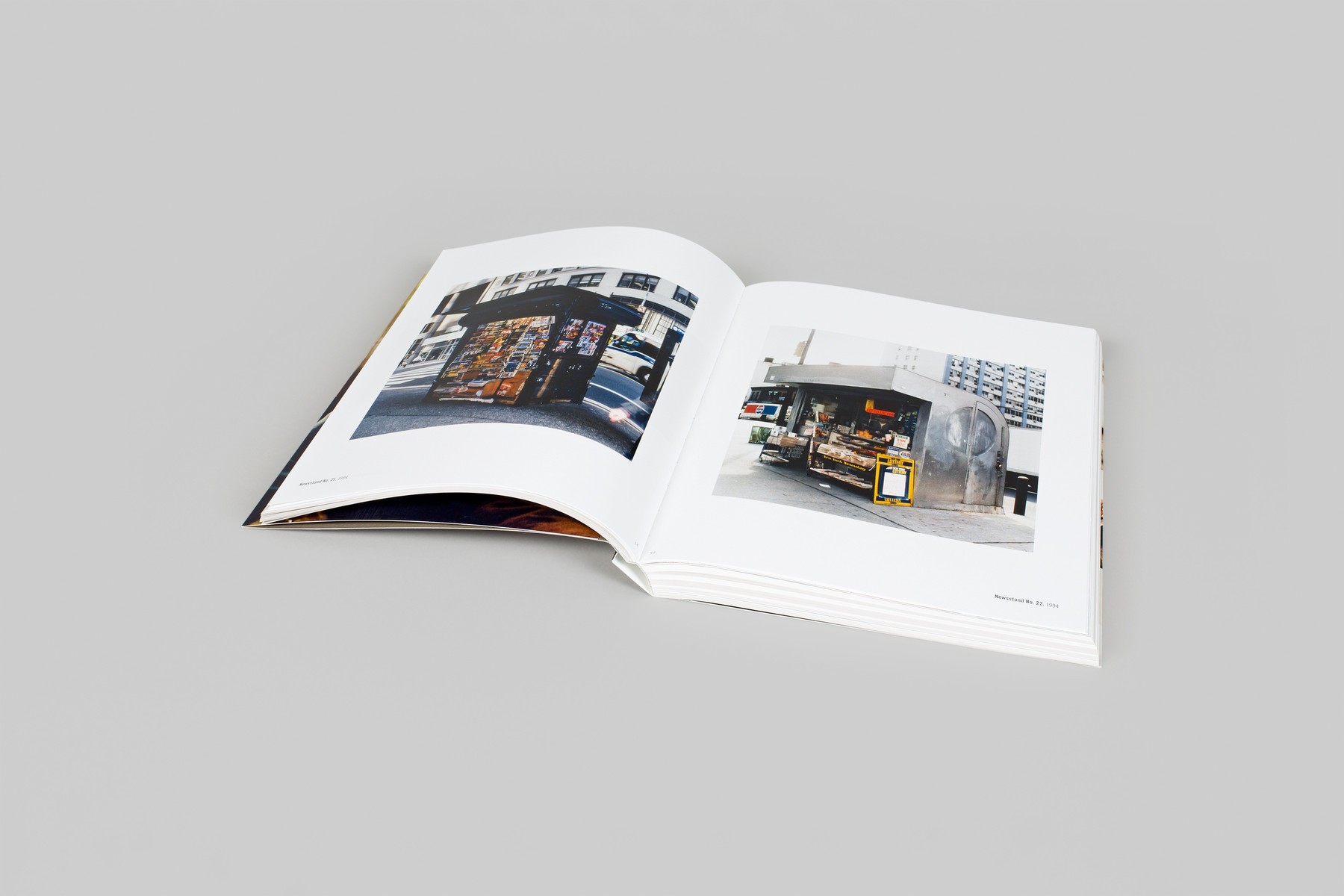

Photographing subjects that facilitate, accompany, or document exchanges has been one way Davey has created this record of intimacy. There are her Copperheads, extreme close-up views of American pennies, Abraham Lincoln’s portrait furrowed with scratches or discolored by human touch. Or her deadpan images of whiskey bottles, each resting in the location where the lat drop was drunk. There are her depictions of the dust and hair that have gathered on the record-player’s needle or under the bed. And of newsstands in New York, their metal roll gates covered in graffiti. Or her recent pictures of receipts for quotidian purchases—newspapers, coffee, records. In these instances, Davey charts time’s passage and hints at the rituals with which, and the people with whom, we pass our hours and days.

Davey recognizes, too, that photographs themselves, like her pictures’ subjects, are tokens of exchange. She has underscored this in recent years by printing her images the size of small posters, folding them up, and sending them through the mail to exhibition venues or buyers, creating what is now a signature presentation format. The photographs, when unfolded, bear the creases, stamps, and other markings of transit. They are addressed, literally, to someone else, so coming across them in the gallery is like overhearing a conversation, being exposed to yet another intimacy.

Davey meditates upon interiority through yet another kind of conversation, often stressing the importance of reading both for her and for her art. And she has responded to that reading by crafting an inspired body of writing on photography, memory, and biography. In essays and video scripts, Davey weaves together her experiences, the lives of kindred spirits, and the theories of influential critics. These texts are not necessarily confessional; what they disclose, instead, is her intellectual temperament, which is both peripatetic and literary.

Davey’s artistic voice is lyrical, inflected by intellectual communion, representative of a hard-won balance between her roles as artist, writer, and, above all, reader.

The figures she weaves through them also haunt her art: philosopher-critic Walter Benjamin, eighteenth-century women’s-rights advocate Mary Wollstonecraft and her rebellious daughters, radical French dramatist and writer Jean Genet, British writer and feminist Virginia Woolf, and others. Davey approaches these touchstones indirectly. As with her photographic accumulations of fragments, she often draws from these writers’ letters and journals, their minor or uncelebrated works, attempting to piece together, in part, how they lived creative, committed lives.

Davey places these lives within a continuum and is adept at highlighting unexpected synchronicities. Through her we learn that Benjamin and Woolf committed suicide “within six months of each other in 1940–41, at the height of personal hopelessness and Nazi terror.” Or that Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Wollstonecraft “were just prephotography, Goethe by only seven years”—a formulation I had never thought to consider. She also places her own family within this same continuum, often noting coincidences that occur to her. Her script for the 2011 video Les Goddesses, for example, includes the following aside, about a Wollstonecraft book: “It was published in 1796, two hundred years before the birth of my son, Barney.” And she relates Wollstonecraft’s parents to her own mother and father; both partnerships produced seven children. As she has said, “The mapping of my circumstances and those of my family onto other genealogies has been my path to storytelling.” William Maxwell wrote about a similar interweaving of life and literature in Woolf’s correspondence: “Books and writers are mentioned and commented on briefly, because how will the friends know what her life is like if they do not know what she has been reading?”

Davey’s predilections as a writer echo those she displays as an artist. Her essays come in fragments, in vignettes. Sometimes the main narrative is overlaid with sidebars created from favorite quotations, which reminds me of how she has hung framed photographs over unframed prints on a gallery wall. Or perhaps the useful analogy is the photographic contact sheet. Each quotation, each meditation, may or may not be linked to what surrounds it, but, taken together, they generate their own logic and reveal underlying preoccupations.

Writing and photographing come together in a recent series that depicts subway commuters recording their thoughts on paper. The subject is a powerful metaphor for being simultaneously alone and with others. Davey’s writers are mostly unaware of her presence, or the presence of those pressed close to them. Yet an aura of concentration does not close them off from others; it connects them more intensely to the people their writing addresses. Davey has noted that she began making these pictures “just when [she had] been writing about the disappearance of the figure from [her] photographs.”

The figure, of course, is not the same as “the human.” Though people did not appear in her photographs for decades, the decisions Davey has made about her work in that time suffuse it with human presence. She has resisted adopting the cold, analytical vantage points made popular in the 1990s by many students of Bernd and Hilla Becher. (She has also avoided printing her work at the superhuman scale those artists often adopt.) She has resisted creating fantastic, surreal constructions that were one response to the postmodern critique of documentary photography. What she has done, and what we can now see properly and begin to treasure, is patiently develop her observational skills. Her artistic voice is lyrical, inflected by intellectual communion, representative of a hard-won balance between her roles as maker and receiver, and between those of artist, writer, and, above all, reader.

Maxwell, like Davey, was interested in biography, memoir, diaries, and letters, and his description of those interests aptly summarizes the subtle power of her work. Davey’s photographs, videos, and writing bring to light “what people said and did and wore and ate and hoped for and were afraid of, and in detail after often unimaginable detail they refresh our idea of existence and hold oblivion at arm’s length.”