Jochen Lempert

Writing,Two Fields Brought Together

Jochen Lempert is doubly open to the world around him. Early in his life, he trained as a biologist, conducted field work in Europe and Africa, and wrote academic papers on various subjects, including dragonflies. A 35-mm camera aided his research. Then, during the early 1990s, he began using cameras as a tool for more creative pursuits, collaborating on experimental films and making artistic photographs. This hybrid background influences many of Lempert’s artistic decisions today. It also makes him a unique figure among contemporary artists: he is as familiar with the ideas of scientists Carl Linneaus and Charles Darwin as he is the work of photographers Karl Blossfeldt, Albert Renger-Patzsch, and Bernd & Hilla Becher. The result is a photographer of nature who is not a traditional “nature photographer,” and a Conceptual artist whose subject matter, techniques, and guiding principles distinguish him from nearly all his peers.

Let’s take two examples. Lempert’s diptych Belladonna (2013) pairs a photograph of the plant, otherwise known as deadly nightshade, and a squirrel. A central dark sphere — the plant’s berry, the squirrel’s eye — links the two photographs formally, and many artists would be content with the juxtaposition. But for Lempert, this is also visual proof of an evolutionary concept. The plant’s berry gleams to attract the fruit-eating animals who can disperse its seeds; each species sees a face in the fruit according to its particular capabilities. This juxtaposition asks us to imagine what the squirrel sees. In other works, such as Formation (2005), Lempert encourages viewers to impose human aesthetic order on non-human species. The triptych depicts four geese seen from above as they float on water. In each picture they form a diamond pattern, and the repetition makes the result seem like the birds intended it. But geese don’t understand geometry, and the impression derived from their relationship is entirely a human projection. By suggesting logic in what is derived from chance, Lempert also nods slyly to John Baldessari’s iconic and self-explanatory 1973 artwork Throwing Three Balls in the Air to Get a Straight Line (Best of Thirty-Six Attempts). In both Belladonna and Formation, the intermingling of scientific and artistic thinking creates a rich set of associations.

Lempert is a photographer of nature who is not a traditional “nature photographer,” and a Conceptual artist whose subject matter, techniques, and guiding principles distinguish him from nearly all his peers.

It’s a wonder that more artists, and more photographers in particular, don’t come from scientific backgrounds. Science is a shifting, evolving discipline — it is never complete — and observation is the scientist’s most important skill. These two facts apply equally to art and artists. Jochen Lempert’s art demonstrates this congruity with quietly spellbinding results.

In the darkroom, in the gallery

Lempert is an analogue man in a digital world. The first thing one notices about his photographs is their peculiar physical presence. In an art world dominated by on-screen JPEGs and the smooth color gradations of inkjet prints, Lempert always works in black-and-white and prints his photographs using analogue techniques. He often manipulates them as he processes them in his studio’s darkroom, and a picture may be printed in four different sizes before the artist settles on which works best.

After a rigorous editing process, during which photographs may sit in his studio for several years, Lempert hangs the finished artworks in a gallery un-matted and unframed. They are taped to the gallery wall in such a way that their rippling edges sometimes lift off its surface. The paper he uses has a relatively loose weave, giving each picture a softer effect; even his most sharply focused images seem, upon first glance, like charcoal drawings or finely detailed pencil sketches. In a world of color prints the size of billboards, the material properties of Lempert’s artworks reveal a sensibility rooted in timeless concerns.

Lempert recombines old and new photographs for each presentation of his work. He worked with the staff of the Cincinnati Art Museum to arrange and mount Field Guide the week before the exhibition opened. As with all his exhibitions, pictures from the 1990s bump up against phenomena he observed recently. This includes pictures made last spring during a visit to the East Coast of the United States and to Cincinnati. Several local organizations — the Cincinnati Zoo and Botanical Garden, the Museum of Natural History and Science at Cincinnati Museum Center, and the Lloyd Library and Museum — generously allowed Lempert behind-the-scenes access, where he made photographs of specimens living and dead, the pages of books in their collections, and the environs.

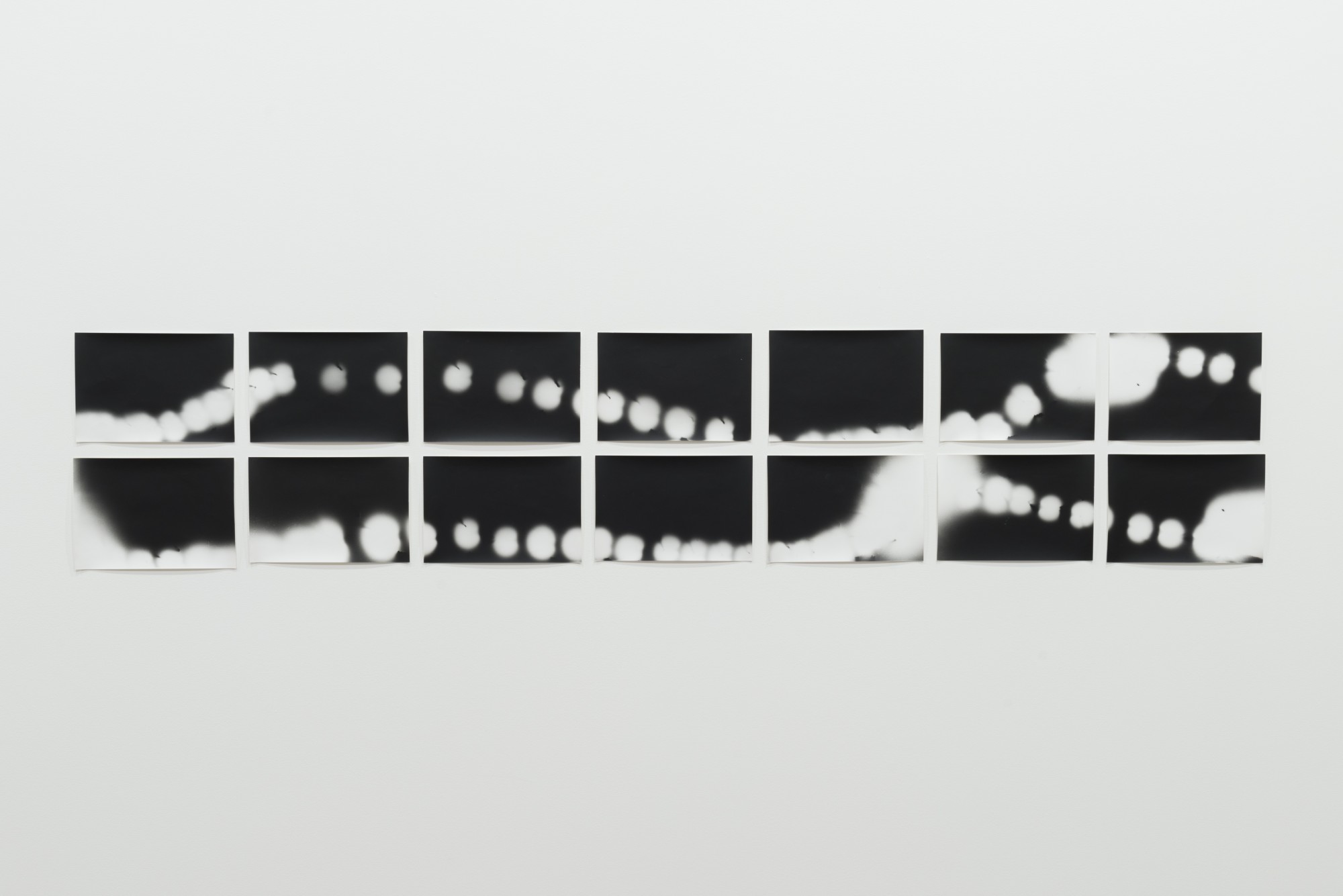

But Lempert can also work in simpler settings. Glowworm (movements on 35-mm film) (2010), was made in a darkened bathroom. He placed a strip of unexposed film on the counter and set the glowworm on it; the insect’s own bioluminescence exposed the film. The line you see, which appears to be an entirely abstract composition, is a direct trace of the worm’s path across four frames of film.

Seeing what can’t be seen

Our ability to observe what surrounds us is remarkable: we peer deeply into outer space and scrutinize sub-atomic particles. These powers are enhanced by technologies that grow more potent with each passing year. Lempert, working with nothing more than a 35-mm camera, cannot capture the heavens or the building blocks of matter. Nonetheless he often tries to photograph phenomena that elude our visual grasp — great spans of time, the complexity of interacting natural systems, invisible biological processes.

Consider Airplane in a Gymnosperm Forest (2013–15), in which tree branches frame a patch of blue sky and a passing airplane. The plane points toward the upper-right corner of the picture, and its implied path connotes the passage of time. But time is marked not only by this left-to-right movement. Scientifically minded viewers will recognize that gymnosperms are among the most ancient seed-producing plants on Earth, believed to have originated more than 300 million years ago. This is, then, a picture of both ancient and modern subjects, and the arrow of time also moves from foreground to background. The photographic instant becomes elastic, stretching across eons.

Other photographs create visual and philosophical puzzles. Even when looking closely at Lempert’s Untitled (shadow on stairs) (2014), it can be challenging to discern whether the stairs rise toward the camera lens or descend away from it. Their sharply delineated geometry is camouflaged by the shadows of leaves that dance across them. Again, Lempert mixes two kinds of order—man-made and natural—to dizzying and visually arresting effect.

Lempert has also photographed the patterns created by raindrops splashing on the surface of a body of water — two impossible-to-visualize systems interfering with one another. He has made pictures of wind and photosynthesis, concepts we understand but can only see through indirect measures. Lempert frequently tests the camera’s vision against the natural world, then encourages us to dwell upon how the natural world trumps human perception and understanding. A sense of wonder at the world’s mysteries rushes into the gap between the artist’s grand intentions and the humble means by which he expresses them.

What is nature?

It’s commonly acknowledged today that no natural environment is entirely pristine, separate from human incursion. Jochen Lempert’s art makes the opposite fact equally apparent: no human environment can be divorced from nature. He finds the subjects of his photographs in an admirably broad range of places. They are not only encountered in the forest or on the open sea, but are also found in dense urban environments. Several of the photographs in this exhibition were taken in Hamburg, Germany, Lempert’s home and a city of nearly two million people. What do these photographs imply about our relationship with nature?

Hamburg has many parks and is situated along the River Elbe, places where one might look for specific plants and animals. But Lempert’s art goes further still. Consider the photograph Vanessa atalanta migration (2014). A street scene taken from the window of a building, its could be from any city: cars parallel parked on each side of the street, a row of residential buildings, some fencing that blocks off a construction project. At the center of the image, however, the camera picks out a tiny butterfly in sharp relief. The photograph, taken from Lempert’s Hamburg studio window, captures the Red Admiral as it passes through town. It took one observational skill to notice the butterfly, and another to identify it and recognize it was migrating — all in the midst of the artist’s average workday.

This picture, and many others like it, suggest that nature is not defined by a place, or even by particular environmental characteristics. Instead, nature is a quality of attention. Look closely, anywhere, and you can find nature. Be patient, be reverent, and its wonders will disclose themselves to you.