Liz Deschenes

Writing,This interview was published in the March 2012 issue of Art in America.

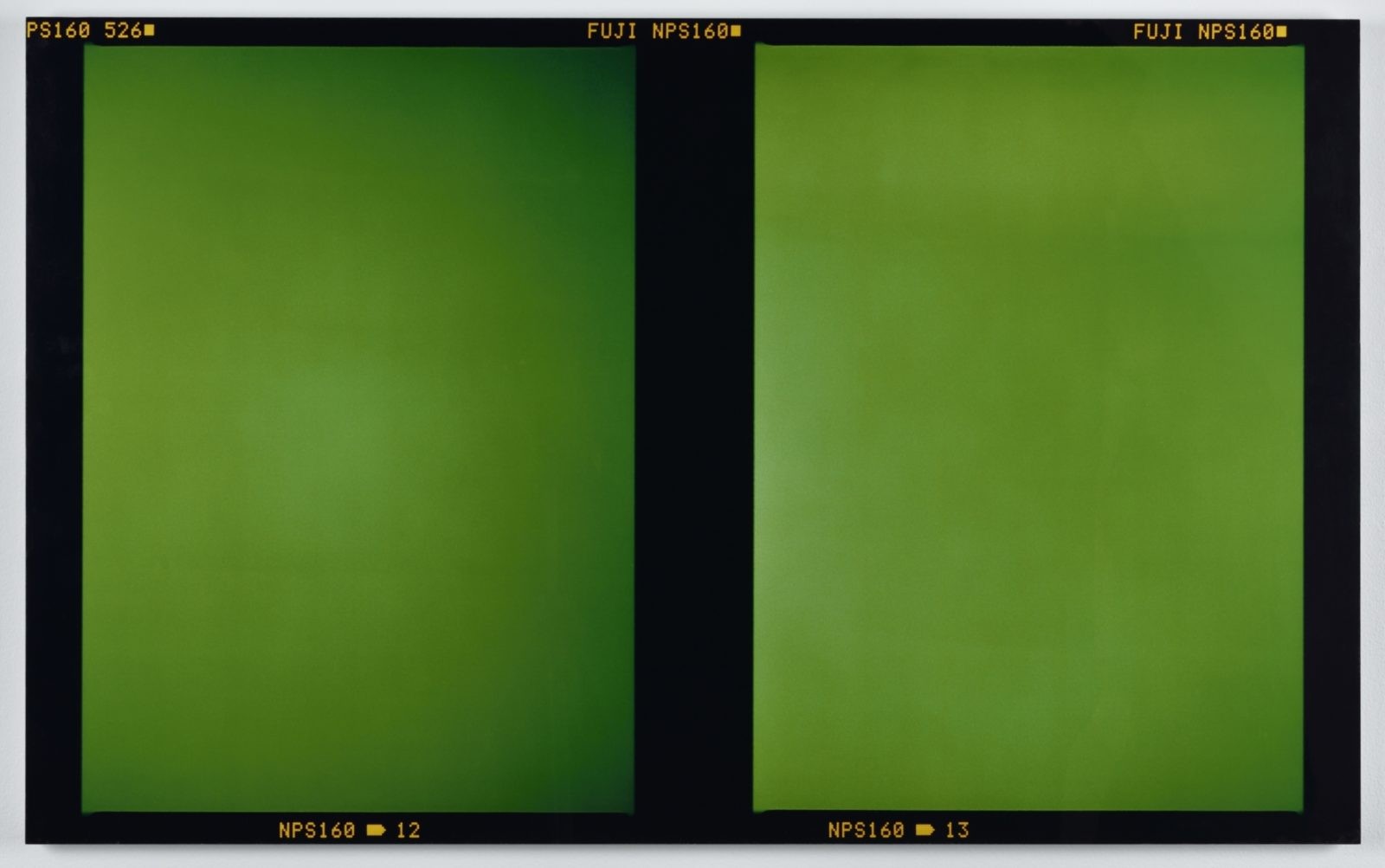

From early experiments with green-screen backdrops to recent, camera-less images made by exposing light-sensitive paper directly to the night sky, Liz Deschenes has persistently explored the photographic image-making process. She isolates the component parts of mechanical seeing and underscores the materiality of the screens that display images. But the loveliness of her artworks belies the astringency this description suggests.

Deschenes (b. 1966 in Boston) graduated from the Rhode Island School of Design in 1988 and has worked in New York since the early 1990s, exhibiting regularly from the end of that decade. She outlined the contours of her practice with “Photography About Photography” (2000), an exhibition she curated for Andrew Kreps Gallery in New York that drew together artists (Vera Lutter, Adam Fuss, Thomas Ruff, Uta Barth) who likewise explore the medium’s mechanics. I first encountered her work in a 2003 exhibition, also at Andrew Kreps, where a selection of her monochromatic photographs illustrated a range of printing and display techniques. These works, in varying shades of gray, were bereft of information when seen from a distance, but upon closer inspection revealed details that hinted at how they were made. One was an image of a plasma television screen (turned off), others photograms made with the light from an enlarger. These works, though conceptually related to their predecessors, seemed far more sober than Deschenes’s earlier, brightly colored images.

As the decade progressed, her work shed external references. Yet from limited means Deschenes creates a visual plenitude. For her 2007 solo exhibition at New York’s Miguel Abreu Gallery, she photographed perforated paper held against a window, then superimposed two copies of each negative in an enlarger to create moiré patterns that were somehow both understated and optically vibrant. Two years later, “Tilt/Swing (360 degree field of vision, version one),” her show of six graphite-colored photograms installed on that gallery’s floor, walls, and ceiling, revealed no image. Yet the installation captured the reflections of the viewers who stood among the works, as if the prints were being continually remade in the image of their beholder. That their untreated surfaces are meant to oxidize, to change over time in response to the atmosphere, adds a sense of romance to the blankness.

As the unconventional presentation of “Tilt/Swing” suggests, Deschenes has added to her explorations of the medium an interest in display strategies. Now she thinks of her work almost exclusively in terms of the other artworks with which it will be shown, and the conditional nature of that approach extends to her studio itself: she doesn’t have a room to which she retreats daily. She divides her time between New York and Vermont, where she teaches at Bennington College, researching and experimenting constantly but making her art on an as-needed basis. At present it’s needed at the Whitney Museum, where she’ll participate in the 2012 Whitney Biennial, and at the Art Institute of Chicago, where she will exhibit in a two-person show with Austrian artist Florian Pumhösl (April 21–September 3). We spoke in January at the CUNY Graduate Center.

Let’s begin with the works slated to be in the Whitney Biennial.

There will be two pieces, both photograms. A four-panel work will duplicate the Madison Avenue facade of the museum building: each element, though turned on its side, will represent one “level” of the stepped facade. The other piece will reference the building’s irregularly shaped windows, in part by reversing their tilt. The surfaces of the facade piece will be silver, though they will not be reflective. The work will, however, change throughout the course of the exhibition. I’m not putting any protective glazing on the surface, so the four panels will oxidize during the show’s run. The piece that reinterprets the windows will be black and will have a shinier, mirror-like aspect.

Allowing one of the works to oxidize has to do with your increasing interest in architecture. Buildings weather over time; spaces show the effects of people’s use of them.

I’m absolutely interested in the conditions of display literally being part of the work, being incorporated into the surface of the work. It’s not incidental that I’ve chosen to make these works for what will probably be the last Biennial in the famous Marcel Breuer building.

Do you conceive of this version of the building’s facade as a kind of architectural drawing or a model? Is it to scale?

It’s roughly proportional; I made each panel a bit longer than necessary to take into account the height of the third-floor wall on which it will be exhibited. I see this work in relationship to both photography and architecture. Architectural photographers can use tricks, movements of the camera, to correct for perspective. That’s part of the reference in this four-panel work, and the other reference is very literally to all the photographs that exist of the Breuer building. I see my work as a stand-in for all of the images documenting the building.

Can you speak a little more about the second work included in the Biennial?

I’m absolutely interested in the conditions of display literally being part of the work, being incorporated into the surface of the work.

Well, it relates not only to the Whitney’s windows but also to my exhibition “Tilt/Swing,” which was very sculptural. Whereas in the earlier show I installed pieces that were not perpendicular to the floor and walls, these pieces will be angled to the wall, though the frames I’m building will make the sculptural qualities less readily apparent.

Is that a way to reassert that you are indeed a photographer and not a sculptor as you increasingly consider architectural questions and investigate strategies of display?

I think it’s more a question of being subtle and asking people to look closely, not automatically revealing everything about each work. There are more connections between the Breuer building and photography. The museum looks like a machine, specifically the Rolleiflex 2 ¼-inch camera, or a 4-by-5-inch camera with its bellows extended. I can imagine the building as a camera or as a kind of photographic installation. The other way in which the building replicates the camera is through the windows, its apertures.

I had wondered whether you had exhausted your interest in the camera and photographic printing technologies. And yet, despite the fact that your recent installations can be conceived of as architectural, you are still nonetheless intimate engaged with ideas of how cameras are built and what they can do—with technologies of mechanical seeing.

Mechanical seeing, yes, but I don’t necessarily utilize the camera to talk about it. I think it’s key that these pieces will also be camera-less pieces.

The camera is a means to an end, but the end is not what anyone would expect a photographer to come up with, in a way.

No, and even photo curators don’t necessarily recognize the end product as being photographic.

You mentioned to me that you’ve been speaking with curators or working with some who mistakenly slow your work in their database of objects as sculpture.

Or as paint or metal—just metal. [laughs] So the thing that’s actually most photographic is sometimes least recognized as being photographic.

Perhaps we can move on to a curator who hasn’t made that mistake, Matthew Witkovsky at the Art Institute of Chicago. Can you discuss the show you’ll be in there and your work for it?

It’s a two-person show with Florian Pumhösl, an Austrian artist who lives and works in Vienna. Before Matthew came for a studio visit last spring, I had laid out tape along the floor in accordance with a Herbert Bayer drawing describing how to move viewers through an installation space. Matt suggested that I could potentially bring together other photographers who were also working in the medium in unpredictable ways and present an exhibition in Chicago using the Bayer drawing as an installation guideline. I worked on that for several months and couldn’t really find a particular reason to bring five or six different artists together other than liking all of their work.

At that point I thought it would make more sense for Matt to take back the role of curator. He decided to position my work alongside Florian’s. Upon visiting Chicago, both Florian and I were, I think, rather take by the differences between the old parts of the Art Institute and the new Renzo Piano–designed Modern Wing. One main reason is that the Renzo Piano walls are, I think, sixteen inches thick and the walls in the preexisting galleries are about eight inches.

And the walls in most other art galleries are only a few inches thick.

Piano’s walls, for whatever reason, are so thick. So with that in mind we were going to re-create parts of the older Art Institute buildings inside the new Modern Wing to draw attention to the different modes of display that have existed throughout the museum’s history. We’re not only bringing the walls from the older parts, we’re also bringing some screens used to block daylight in the McKinlock Court to the Modern Wing as well.

And this exhibition will include works from the photography collections of the museum, so your contribution will be framing devices of sorts, meant to contextualize or bracket both Florian’s work and the collection’s work.

That’s a good way to describe it. I think I’m only going to have two pieces that will be nestled in corners. I’m not sure what the proportions of those pieces will be, but in these corner pieces I might replicate an interval system Piano came up with for the Modern Wing that is based on a 6 ¾-inch unit used in various architectural elements.

His version of the Golden Ratio, so beloved by Le Corbusier.

Yes. It’s human, but substantial.

You mentioned having had a studio visit with Witkovsky. Yet you and I are sitting in a lounge at a university and not an artist’s studio. Can you describe a little bit of your working process? Even without a formal studio there are haptic, tactile, studio-like aspects to how you come up with these pieces and their specific properties.

Of course, there’s a deep research component to the work, some of which takes place in terms of teaching, at Bennington or elsewhere. I build scale models for all of the exhibitions in which I participate. The Usdan Gallery at Bennington is actually based on the third floor of the Whitney building, so instead of using a foam-core model I used a model that as built in the early ‘70s—

That you can walk into!

—that I can walk into and actually feel the proportions of the work. The initial proportions I came up with for the four-panel piece were too wide for the space, so I narrowed them down. And returning to my interest in pedagogy, I think the Art Institute exhibition points to those concerns. Using the Breuer—er, the Bayer—I can’t believe I just confused them! They weren’t close friends. Using the Bayer drawing to guide people through space and asking them to look at the walls in a new way touches on this. And of course what gets installed on those walls will be equally crucial to understanding the exhibition, and I like that a lot of those decisions haven’t yet been made. The walls are being built right now, but I won’t know until I actually go to Chicago what work gets installed, so there is an aspect of spontaneity that frees me from a daily studio practice. I’m more interested in responding to the conditions of exhibitions. As they change, I can change along with them.

I constantly have to respond to the changing conditions of the work, which is part of the reason why I’m trying to make work that also changes during the exhibition—and beyond. Because there is no decisive moment.

Your “decisive moment” happens during the installation process?

No, it keeps on happening. I constantly have to respond to the changing conditions of the work, which is part of the reason why I’m trying to make work that also changes during the exhibition—and beyond. Because there is no decisive moment.

You also mentioned pedagogy. For a long time you were learning new things about photographic technology, but now it’s also as if you’re trying to give yourself an autodidact’s M.Arch. degree. Reading new kinds of drawings—plans, axonometric views, and so one—almost entails a new way of seeing and thinking. Is that a fair characterization of what you’ve been up to in recent years? And, if so, does that impact the ways that you think about the field of photographic image-making that you know so well?

That’s an interesting question. Earlier I described the Whitney photographs as being stand-ins for the building. The building will obviously continue to exist, but as a newer or different institution. So to actually put scaled photographs representing the facade in the interior of the museum is a way of repositioning what you would generally find outside of the museum. I don’t necessarily need to understand the things that Breuer had to understand in order to build that building. It’s more about trying to understand photography through architecture.

Let’s talk a little bit about Herbert Bayer, who was one of the last surviving members of the Bauhaus. He was known most prominently neither as an architect nor as a photographer but rather as a graphic designer and a type designer. You’ve latched on to an ancillary aspect of his practice to explore for your own purposes. How did you first come across his work?

It was when I studied with the historian Mary Anne Staniszewski at Rhode Island School of Design, and she published a book on the history of installations. It was in her text that I found the drawing from his idealized 360-degree viewing that I later used as the basis for my 2009 exhibition at Miguel Abreu.

I have no idea where this investigation will go. It’s becoming looser and looser. The Art Institute of Chicago is not a direct iteration. In the drawing, Bayer has a beginning, a middle, and an end to the viewer’s path. I likewise tweaked the 360-degree viewing drawing; it was a collapsed space that I expanded outward for my installation. I’ve taken a lot of liberties with Bayer’s drawings, mostly in an attempt to be less controlling about how people move through the installations.

Is that because you’re more confident in being able to communicate through your objects? Or are you just mellowing as you age, spending more time in Vermont?

[laughs] I trust that people can determine their own beginnings, middles, and ends and their own sense of whether they want to be inside a piece or outside a piece.

And their ability to stitch together a meaningful experience from that.

I think people can find their own vantage points.

Over time I’ve been able to remove some of the more peripheral or external concerns that I previously used to give people access to my work.

In our earlier conversation, you chafed a bit at the fact that your work has been corralled into discussions of photographic abstraction. Though many of your works are monochromatic, they’re not necessarily abstract. So how else can we categorize your practice? Given your interest in strategies of display, would site-specific be a better term—or site-responsive, medium-specific?

During our last conversation you asked me when the break happened between earlier explorations of the medium and the larger questions about installations and space I’m addressing now. I think both aspects of my practice have always existed. Over time, and through the accumulation of installations, I’ve been able to remove some of the more peripheral or external concerns that I previously used to give people access to my work. My first exhibition contained seven monochromatic dye-transfer prints. I think if I hadn’t included landscape references, there would have been virtually no point of entry for the viewer. The images corresponded to—or were literally stand-ins for—topographic maps, so they went from a sort of cyan-ish green, which would represent sea level, to a dark brown, which would represent the tallest mountains.

One additional reason I’ve been able to eliminate some of the easier access points to my work is that other artists have opened up in the public’s mind new ways of thinking about photography. A lot has shifted since I curated an exhibition in 2000 of photography about photography. The discourse then was entirely narrative, and now it’s not. That means things like color no longer need to be a dominant force in my work. I don’t work with a camera really at all anymore, except to document views while doing research. I would describe my trajectory as more of a narrowing than a broadening of concerns.

You’ve been kicking away the props. It’s gotten to be almost pure image-making.

I should emphasize that I needed those things, too. Creating a seventeen-foot green-screen backdrop over a decade ago helped me to think these past few months about the Breuer building, and about the Art Institute of Chicago. All those “props” didn’t function solely for a viewer, but also helped me to advance my work.

Is the logical end point to this now two-decade-long progression to stop producing new objects? There’s a slightly puritanical aspect to this investigation of mechanical image-making, an obsessiveness that has as its terminus a kind of zero point.

Well, every single time that I’m about to finish a project, I think to myself, this is it. I’ve been saying that for over sixteen years. If the past is any indication of the future, the work will continue to look at the conditions of display, which are obviously constantly in flux.

This leads me back to the earlier question about studio practices, because that anxiety sounds like what any artist feels in her studio. Yet for you the will to go on is rooted in responding to other viewing experiences, not in, say, fighting with a canvas. Is your “studio” in part the time you spend looking at and thinking about other art and architecture?

Yes, and reading and listening to lectures and researching for my courses. Others would say something similar about their studio practice, but in addition I wonder whether it’s important that my work look a certain way. Have you seen Sherrie Levine’s exhibition at the Whitney? In a recent panel discussion, [curator] Elisabeth Sussman said that throughout the entire curatorial process Sherrie did not discuss one aspect of her studio practice. As though it didn’t exist.

Or as if Levine was curating somebody else’s work.

And Elisabeth and Johanna [Burton, guest curator] likely deferred to Sherrie. And in that show there’s no interpretive wall text. So that would be the … I don’t want to say goal, but not to have to talk about how the works get made would be great. I’m much more interested in talking about my work in relationship to the work it gets exhibited with. So much of what I’m making right now is intended for the group-show context. The corner pieces were made specifically for a group show. I want the Whitney pieces to correspond not only to the architecture but also to the other artists’ work. That wasn’t a though that I could have had ten years ago. It was only after multiple experiences seeing my work isolated and decontextualized that I thought it made more sense to explicitly create art meant to be in dialogue with other people’s art. That’s probably the biggest shift in the work—one that probably nobody could see but me.

But that runs counter to your description earlier of an increasing laxity on your part, or your ability to be more relaxed about people’s ability to interpret your objects. The control that you used to hope to have over viewers, you’re not placing over yourself in a way. You’re making your practice conform to each of these exhibition contexts. If Witkovsky said, “Actually, let’s work with my colleague in classical sculpture,” what you would make would probably be entirely different from what you would make for your two-person show with Pumhösl in the photography galleries.

I would say that’s really accurate, and I would say that’s probably where the studio resides now: in proposals.

One of the elephants in the room in discussion of photographic technology is new media. Whereas many people have struggled with the transition from analog to digital, your way of inventing a new studio practice for yourself snuck you past such questions. It was a way to move forward while still exploring analog photography.

Well, for example, my 2001 exhibition “Blue Screen Process” at Andrew Kreps Gallery was about the compositing process as it evolved from the 1920s to the present day. In one series of work I basically covered all of the material possibilities of compositing. Since then new technologies have evolved; the one thing that has always been true of photography is that the technologies have always shifted and changed, digital or no.

Now I’m envisioning the blue screen (or green screen) as a kind of metaphor for your practice as I was describing it earlier: There’s Liz Deschenes standing in the image, in the middle, and the background keeps changing, the context keeps changing.

That’s a nice way of looking at it. I also don’t necessarily look for particular projects, either. I’ve been really, really fortunate that most of the dialogues that I’ve had with other artists have arrived when they needed to arrive. I’ve been familiar with Florian’s work for a really long time. Now I get to do a project with him in Chicago.

I would say that’s probably where the studio resides now: in proposals.

So the end point I mentioned earlier doesn’t come through technological exploration, it occurs only when opportunities to reinvent yourself stop arising. But they continue to.

But the change, too. Florian and I showed together at the Forum Stadtpark, in Graz, Austria, in 2003, in an exhibition called “Rethinking Photography.” I don’t necessarily think that such a context is as important today as it was then.

Can you envision a time in which your practice is primarily curatorial?

I don’t think—I don’t think that would be—

You’re still too attached to photography itself, to the medium and practicing it?

I think the two modes of working can coexist. Even though I didn’t want the title “curator” for what I’m doing with Matt and Florian in Chicago, there will certainly be curatorial components to it. I don’t really see a huge separation between exhibiting, researching, teaching. All the facets overlaps and photography is—has been—the word that contains all aspects of my work.

Photography is the container.

And I think photography is the perfect container. It has constantly shifted and changed as a technology, so it’s a perfect stand-in for all aspects of the work I do.