The USS Recruit As a “Non-Site”

On a wartime intervention in New York City’s public space

In graduate school I spent a fair amount of time researching how public spaces were used for political purposes during the Progressive Era. In particular I looked at New York City during World War I. Despite there being, to my knowledge, no large-scale permanent memorial in New York to the American war effort, the spaces of the city were dramatically reshaped during the war itself. In early 2012 I was invited to give a talk to an art-world audience on a subject outside my area of expertise. So I took an excerpt of a paper I was then writing, removed some scholarly language, and added in some references to Learning from Las Vegas and Robert Smithson. I remain fascinated by the subject, so I thought I’d share it here.

Some time ago I came across an image in a scholarly article on the history of Union Square that piqued my interest. I’m training to become a historian, so I know how to pursue these things when I come across them. This image suggested an opportunity to explore questions that always intrigue me: How is public space governed? Who has access to it, and what messages are communicated by its design? How does its usage change over time, and what characterizes its use at times of social stress? I don’t yet have the skills necessary to pursue the answers to such questions at dissertation length. I sometimes revert to the language of architecture and art criticism I developed in my near-decade as a reviewer and magazine editor. Nonetheless, what follows is an initial attempt to think through the implications of that image. First, a little context.

President Woodrow Wilson asked Congress to declare war on Germany on the evening of April 2, 1917. It was the fifth time that year he had spoken to Congress about the war in Europe, a reflection in part of the increasing belligerence toward the United States by the Germans, who had announced unrestricted submarine warfare against American ships that February. Two years earlier the Germans had sunk the British ocean liner RMS Lusitania, killing nearly 1,200 people—including 128 Americans, which provoked many in this country to call for retaliation. Despite such German aggression, Wilson had counseled patience for years; in 1916, his re-election campaign slogan was, “He kept us out of war.” Wilson was being so patient, he wrote to a friend, because “it was necessary for me by very slow stages … to lead the country on to a single way of thinking.” Americans, many of them a generation or less removed from countries engaged in the conflict, were deeply divided over whether the United States should join the fight. By early April, however, opinion was united enough that Congress could pass a war resolution with overwhelming majorities: 82 to 6 in the Senate, 373 to 50 in the House of Representatives.

Despite a war-preparedness movement that had been active for several years, when Congress declared war the United States was in no position to launch a major campaign across the Atlantic Ocean. Entry into what was already known as the Great War presented an unprecedented logistical nightmare. For example, the federal government planned to build the largest shipyard in the world just outside Philadelphia. Called Hog Island, it was to be larger than Britain’s seven largest shipyards combined, and would employ 34,000 workers. But construction of Hog Island led, in late 1917, to what was known as the “Great Pile-Up.” Railroad cars delivering wood, steel, and other construction materials clogged the tracks leading to Philadelphia. With nowhere else to go and not enough workers to unload all the arriving cargo, conductors abandoned their trains. The railroads backed up to Philadelphia, then to Pittsburgh, then all the way to Chicago in what was perhaps the worst traffic jam in human history. On January 1, 1918, Wilson nationalized the railroads in order to help solve the crisis.

The logistical nightmares involved more than supplies; they also involved people. In asking Congress to declare war Wilson forcefully suggested that he would institute a draft to meet the required manpower levels. It was a controversial decision, and one result of the controversy was that conscription would only apply to the new National Army raised for the effort. The Navy, the Marine Corps, and the National Guard needed to increase their troop levels for the war through volunteer registration.

The largest cities were expected to provide the largest number of volunteers. These metropolitan centers, however, were often home to the most recent immigrants—those whose loyalties to the United States, it could be said, were least developed—as well as the conscientious objectors and political radicals who were against the war as a matter of principle. Within weeks of Congress’ declaration, New York City mayor John Purroy Mitchel recognized that without his significant intervention the Big Apple would fall well short of its quotas. He had already organized a Committee on National Defense, and it was with this group of advisers that he set out to ensure New Yorkers would play their proper role in the American war effort.

Just three weeks after the declaration of war, The New York Times quoted the mayor as announcing: “The committee is now engaged in general supervision of various plans for promoting recruiting for the army and navy, and in particular the construction of a replica of a battleship in Union Square, which will become the headquarters of recruiting for the navy in this general territory, and which we believe will serve as a very material stimulus.”

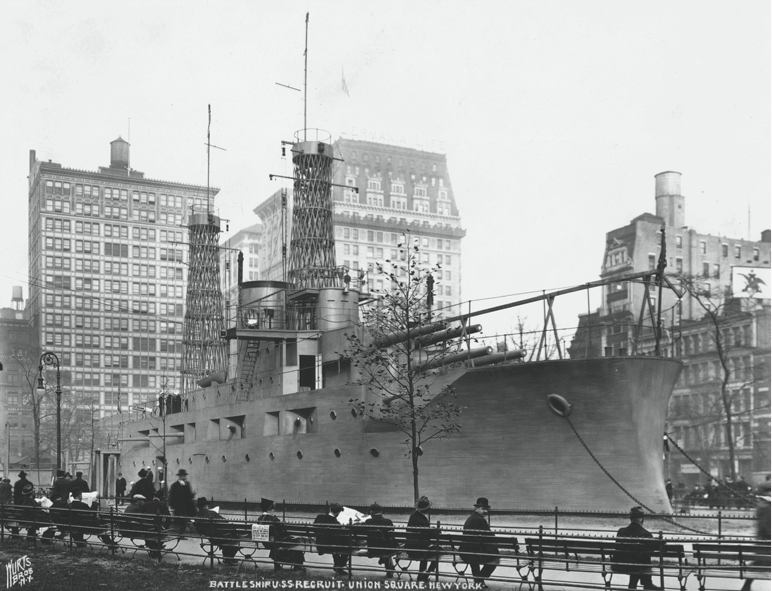

A battleship in Union Square? Here is the image that first caught my attention. Within four weeks, a two-hundred-foot-long by forty-foot-wide wooden replica dreadnought was drydocked in one of the city’s most famous public spaces. Built at a cost of $10,000 ($168,496 in 2010 dollars), it contained, and here again I quote from the Times, “a spacious waiting room for recruits and applicants, physical examination rooms, both fore and aft; doctors’ quarters, shower baths, and numerous other accommodations for officers and men…. The main deck will be fitted out after the fashion of a battleship from turrets to awning rails. A number of machine guns have been sent over from the Brooklyn Navy Yard, which will be manned by regular gun crews prepared to give instruction.” The whole ensemble, reported the newspaper, “is expected to bring the arrival of war directly home to the people of the city.”

Many historians have chronicled the efforts of George Creel, a public relations and advertising whiz hired by Woodrow Wilson to run the Committee on Public Information—the government’s wartime propaganda arm. He masterminded an expensive and enormously successful campaign to publicize the war, and it’s easy to see how Mayor Mitchel’s efforts to increase enlistment are related to the Committee on Public Information’s posters, movie reels, liberty bond drives, and parades. Evidence exists that the USS Recruit fits into such a narrative. Films and newsreels were projected onto it for appreciative audiences. Society ladies released from the Recruit homing pigeons with messages for the White House affixed to their legs. Vaudeville skits were performed on deck. Marine bands performed compositions by the “American March King,” John Philip Sousa, and theater groups gave renditions of Gilbert and Sullivan plays. Blaine Ewing, the man on Mayor Mitchel’s committee responsible for its construction, was quoted in the New York Tribune as saying, “This big ship is advertising propaganda, pure and simple.” Yet something about the USS Recruit seems different, and far stranger, than the typical propaganda Creel churned out via the CPI.

What must life have been like for the eighty-seven naval officers stationed “aboard” the USS Recruit? The boat was more or less life-size; the guns on its deck, though their barrels were sealed, were real. These men were expected to maintain their normal routines, looking after the ship as they would were it out at sea: They would “arise at six o’clock, scrub the decks, wash their clothes, attend instruction classes, and then stand guard and answer questions for the remainder of the day.” How did it feel to pantomime the vital war work being undertaken by their colleagues off the coasts of Europe? Was it difficult for their officers to convince them that what they were doing fulfilled the dreams of patriotic service that led them to sign up for the Navy? I imagine their day-to-day experience was akin to Bill Murray’s in the movie Groundhog Day. Each morning they would stand on the deck and look over the rails at the same scene: a bustling urban intersection, ringed with newly erected ten- and twelve-story buildings, crowded with pedestrians.

Among those pedestrians must have walked socialists and other antiwar radicals. The Socialist Party, which had officially taken a pacifist stance, operated the Rand School, a bustling and popular education center, on Nineteenth Street, a few blocks northeast of Union Square. The square itself was the traditional New York home to labor rallies, anarchist demonstrations, suffragette parades, and other forms of dissident public agitation. On May Day 1912, labor radicals and socialists had torn down the American flag displayed on the cottage at the park’s northern end, and in 1908 and again in 1914 bombs were detonated as policemen attacked rallying workers. What did such men and women feel as they climbed out of the subway and into the shadow of an overbearing spectacle representing all they disagreed with? The decision to locate the Recruit in Union Square feels pointed to me in a way I have not yet been able to trace.

Adding to the swirl of mixed feelings was the ship’s design, which was masterminded by the architect Donn Barber and the illustrator Jules Guerin. In the 1960s, the architects Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown, and Steven Izenour proposed the “duck” and the “decorated shed” as the two main manifestations of the contradiction between image and the uses of a building. The duck is the special, and increasingly rare, building that is a symbol. What did the Recruit’s design symbolize? It was first and foremost an expression of naval power. More specifically, however, the Recruit was modeled on the USS Maine, the American warship that had exploded in Havana Harbor on February 15, 1898. Although no evidence was found that the Spanish, who were then fighting against a Cuban independence movement, had attacked the Maine, suspicion about the explosion led to jingoistic cries that America enter that conflict. New York newspapers owned by Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst led the outcry, which indeed helped push us to war two months later. How many New Yorkers who visited or saw the Recruit recognized in its profile the ship that had been plastered on their front pages day after day two decades earlier? How many were moved or reviled by its invocation of that earlier moment of martial spirit and patriotic frenzy? Blaine Ewing, of the mayor’s Defense Committee, said, “Of course, we might have built a big shed in Union Square that would have served the purpose.” But he recognized the power of the “duck,” so he created one.

A large difference between general wartime propaganda and the USS Recruit, to me, hinges on what the New York Times described as “bringing the war home.” The USS Recruit was a spectacular weapon in the battle to win New Yorkers’ assent to the war. Yet it was also a material intervention into one of the city’s most hotly contested public spaces, an island in an archipelago of militarized sites that formed a wartime city within the city.

In November and December 1917, Grand Central Palace, a recently constructed exhibition hall at Lexington Avenue and 45th Street, was given over to HERO LAND, a sixteen-day extravaganza billed as “the greatest spectacle the world has ever seen for the greatest need the world has ever known.” Among its exhibits was an exact reproduction of a segment of the trenches along the Flanders Front. Four months later, in the spring of 1918, a plan was put forth to dig more trenches in Central Park. A huge public outcry led, in early April, to the abandonment of that plan, but others succeeded without incident, changing the face of the city. Fifth Avenue was essentially appropriated for the course of the war, home to so many parades and processions it could have been renamed Patriot Boulevard.

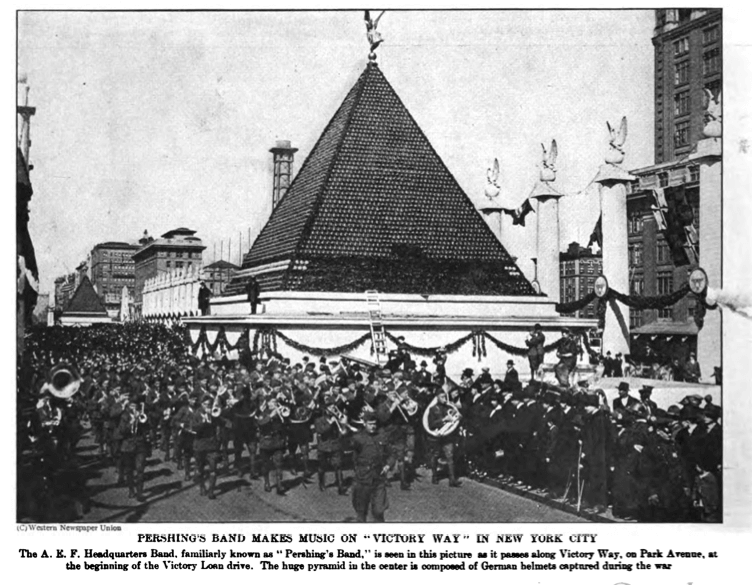

This was, as I have suggested, an essentially theatrical presentation of the war, and part of an ongoing contest to redefine the city’s public spaces in light of the war effort. “Bringing the war home” was made literal, however, as objects used in the prosecution of the actual war were put on display in New York. In early 1918, a British tank christened the Britannia was placed in Union Square, next to the Recruit. One fine spring afternoon its officers climbed in, closed the hatch, and took it for a drive over the Brooklyn Bridge; a party of dignitaries met it at Borough Hall. That same year a captured German U-boat was hauled out of the water and put on display in Union Square, testament to America’s ability to reverse the momentum of the conflict. In spring 1919, after the war’s conclusion, a pyramid made of captured German soldiers’ helmets was placed on Park Avenue just north of Grand Central Station.

I envision these objects as akin to artist Robert Smithson’s non-site sculptures. Smithson dragged rocks, dirt, and other geological materials from locations in New Jersey to art galleries or museums in various cities, creating a perpetual and open-ended dialogue between here and there, open and closed, edge and center. His objects were “three-dimensional logical pictures” representing a place inaccessible to his viewers. The United States military dragged tanks and submarines to the contested public spaces of the country’s largest city to represent a place—and a way of life, that of the soldier—inaccessible to its residents. Setting them down next to the enormous toy ship must have added even more to the incongruity to the scene in Union Square. Smithson wrote, “between the actual site … and the Non-site … exists a space of metaphoric significance. It could be that ‘travel’ in this space is a vast metaphor.” What convoluted metaphoric significance were the Mayor’s Defense Committee and the US Navy trying to communicate from 1917 to 1920? And how did carting the whole thing off to Luna Park at Coney Island, as happened in late 1920, change the meaning of the Recruit? I haven’t yet developed a satisfactory answer to these questions, but I know that Blaine Ewing’s claim that the Recruit was “advertising propaganda, pure and simple,” does not suffice. Trickier questions about contesting claims to public space, the connection of civilians on the home front to combatants, and the relationship of New York and other large cities to federal campaigns need also to be answered.